How Will We Know When It's Working?

how will we know when the New Disorder is over?

“Optimism” would not be the right word to describe a particular cultural current I’ve felt lately, but it’s not far off. Recent conversations; things I’ve read; things I’ve listened to - in all of them, I’ve found a theme of seeing the other side of this wretched American moment. My friend, the political/public affairs consultant and noted Philadelphia boulevardier Dan Siegel, put it extremely well: “I’m bullish in the medium-and-long term…assuming we make it through the short.”

None of the people I have spoken to (including and especially Dan), or whose words I’ve read or listened to, trivialize the danger of this phase of American life, or the unspeakable harm that will certainly be done before we are through it. In all of these conversations and pieces, you can feel the grief that our polity has come to This.

And yet also, there is hope (which, the organizer Mariame Kaba reminds, is a discipline), a clear sense not that this gruesome moment will end and we’ll be able to patch things up and carry on as before, but something simultaneously better and more frightening: that the vile, oafish political and cultural tendencies that have brought us to this will collapse or at any rate ebb, and we will have no choice, really, but to build something new to replace what was destroyed. That process has already begun.

I’ll write more on why I think we (people of good intent, for ourselves and others) will prevail, and what that will look like; I’ll cite my examples, and tell the story properly. For now, as I return from my wee sabbatical, please step with me into the future, after This Moment has passed, so we can explore a small example of how we’ll know when the New Disorder1 is over, and that whatever we build in its place is actually working.

**

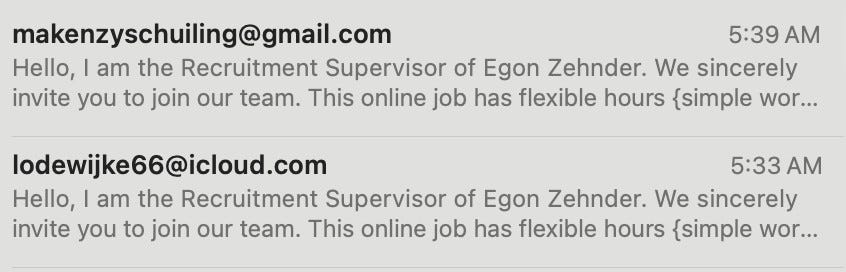

Last week I received the following communications on my phone:

I mean, look at this shit. The absolute state of it.

I am not a proud man. I don’t expect to be able to use any internet-enabled device without immediately becoming the target of half the scammers under the sun. But I do ask that they put a little backbone into it, you know, a bit of elbow-grease, as opposed to sending identical and conflicting below-replacement-level scams to my phone before I’ve had my coffee.

Perhaps, years from now, I’ll look back on this as the absolute nadir of the New Disorder, an obvious sign that our culture and politics have become so flooded with slop (AI-generated and manually-harvested) that even the scammers have given up. No invention, no fresh and energetic attack on our brain’s natural defenses against trickery, just some depressed aspiring thief pumping out transparent horseshit in vast quantities and hoping a stranger will fall for it in a moment of distraction. Grim days for the yahoo boys, it would seem.

But not just them! Maybe you saw the sign of my own capitulation to the New Disorder a couple of paragraphs ago?

Here it is: “I don’t expect to be able to use any internet-enabled device etc. etc.”

Of course I should expect to be able to have a phone without being relentlessly scammed. Any one of us should reasonably expect that merely having access to the internet (a load-bearing part of life in virtually every nation on earth) would not definitionally create an expressway for thieves straight into our homes and indeed right up to our very persons. And yet here I am, blithely forsaking that perfectly human expectation and cynically making light of the idea of ever having had it. Outrageous!

Worse, of course, is that this kind of scamming not only continues but thrives, often using methods significantly less oafish and more devastating than whatever the hell those fake recruitment texts I got were. The cost of these things is high - billions, in dollars, and thousands, in lives taken or ruined, every year.

Nevertheless, they persist. They proliferate. Not because curtailing them is impossible, but because it is hard. Cutting down on scammers’ currently-unfettered access to essentially the entire population of the United States would require at least four things:

A current understanding of communications technology. We are only four years removed from Senator Richard Blumenthal asking then-Facebook’s security chief “will you commit to ending finsta?” Laudably, he was trying to pin her down on what now-Meta would do about child exploitation and bullying on social media, but a “finsta” was simply internet short-hand for a fake Instagram account; it’s not something Meta was doing or could reasonably commit to ending. To be clear, Blumenthal’s understanding of the issue was and is more sophisticated than his question suggested, and he is also just one legislator. But the episode is emblematic of a problem that has been described to me in various ways for the last fifteen or so years but which essentially boils down to the need for a officials from generations who merely adopted digital tech to make rules governing people who were born in it, molded by it. (I am not proud that I said that out loud in Tom Hardy voice alone in my office, nor am I ashamed. Judge me if you must!)

The last piece of major federal legislation on this issue was passed in 2019, and it made it harder for scam calls to hide the number they were calling or texting from, but - functionally - did not make it any harder to actually execute the scam itself. The Biden Administration, to its credit, attempted an enhanced regulatory response; you can imagine what’s become of that. The kind of sustained focus and topical fluency required to legislate and govern on this issue do not usually come about without profound political pressure. SPEAKING OF WHICH.

A willingness to fight with telecomms and Big Tech. Both telecomm companies and tech companies with messaging/social media services have taken a variety of steps to reduce scams that use their products, but the scale and adaptability of scamming as an industry requires a constant and fully-resourced response that, bluntly, no one on the private-sector side has felt obliged to provide because they don’t actually lose any money because of it. It’s just a form of customer service to them, a cost-center. If they are going to adopt a constant, agile, and full-scale response to scamming, it’ll be under compulsion by rule of law. At the moment the record of elected officials to compel either telecomms or Big Tech to do anything is pretty damn spotty.

The ability to cohere an international response. Several responses, really, because while in theory almost anyone with the right knowledge and tech can set up for a scammer, in practice, phone scamming tends to be conducted at-scale by organized criminals either evading local law enforcement through bribery, trickery, and menace, or who have set up where there just isn’t much law at all. The infamous “pig-butcher” scams (you’ve probably gotten the first nibble of one of these before - it’ll be a truly surreal “wrong-number” text message designed to start a conversation; my personal favorite was just a photo of a hand holding a bottle of wine) are conducted in what amount to outlaw settlements in eastern Myanmar, full of hundreds and indeed thousands of people trafficked from China and other parts of Asia, and who are functionally enslaved. Breaking up just those operations would require diplomatic, law enforcement, and possibly military coordination with China, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar - just to start with. It’s doable (indeed, it has been done), but, again, it’s hard.

Giving a shit. This is, obviously, the prerequisite for any of the above, and it’s why nothing will be done until this particular Political and Cultural Moment passes. The Trump Administration has reportedly ordered 1/3 of the FBI’s manpower diverted to assist with its farcical and inhuman crackdown on undocumented migrants, and away from actual crime; not to overstate the case, but I’d be less surprised if the larger Trump apparatus started a pig-butchering scam of its own than I would be if they actually broke one up.

But! This Moment will pass (which, again: more on that later). We will be called upon to build something new its place. How will we know we have succeeded?

One good sign will be when the next iteration of American political power (and it will be from that sector that the solution emerges) genuinely curtails scammers’ access to our phones, computers, and indeed brains, for no reason other than the fact that ordinary Americans are being variously annoyed, pilfered, and outright ruined. It’ll require focus and expertise; a willingness to fight and corner some truly gargantuan corporations; and the ability to bring together international partners of varying capability and good will.

But it is doable, and worth doing. That should be enough.

It’ll be a small change in our lives - one of many that will tell us something much bigger has shifted under our feet.

The New Disorder, you’ll recall, refers to the present cultural, political, and financial circumstances, in which a series of institutions and individuals fundamentally, serially, and baroquely failing to meet the expectations of the majority of the people whom they notionally serve.